The Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater (REDCAT) was the venue where the collaborative team of David Roussève/Reality premiered its strong, but uneven production of Halfway To Dawn. I say uneven because, although it was beautifully structured and the transitions from one scene to the next were seamless, it is my opinion that the first act needed serious editing. Act Two was powerful, haunting and tragic; and it moved effortlessly like a brilliantly written play.

Halfway To Dawn is a dance-theater piece. It is a dancing tribute to the music of jazz legend, Billy “Sweet Pea” Strayhorn (1915-1967), and an abstract theater portrayal of the ups and downs of his life and career. Strayhorn was an openly gay African-American man during an era where a gay lifestyle was far from safe. He worked and collaborated for many years with Duke Ellington without copyright protection or even sometimes receiving printed acknowledgement of his work. He started with Ellington in 1939 but it was not until 1956 that he received copyrights to his songs. In addition, Strayhorn was a passionate activist and supporter of Martin Luther King during the civil rights era.

Although it is not widely known, Strayhorn was Ellington’s main arranger and writing partner, writing arguably Ellington’s most famous song Take the A Train (1939). The title refers to the then-new A subway service that runs through New York City from eastern Brooklyn up into Harlem and northern Manhattan. He worked closely with many jazz greats; his closest professional and personal relationship being with the iconic singer and actress, Lena Horne. The list of his compositions is too extensive to include in this article, but in 1946, Strayhorn received the Esquire Silver Award for Outstanding Arranger.

A heavy smoker and drinker. This was demonstrated throughout Act Two with repetitive video projections of a burning cigarette, champagne flutes clinking together, and whiskey being poured in a glass. As a result, Strayhorn died at the relatively young age of 51 of Esophageal cancer. Ellington wrote, “….Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brainwaves in his head, and his in mine.” Following Strayhorn’s death, Ellington produced a tribute album to his long-time friend and partner titled …And His Mom Called Him Bill (1967). It brings to question, however, why Ellington waited so long to give Strayhorn full credit for his work.

David Roussève is the recipient of numerous awards including a Bessie (New York Dance and Performance) Award, Creative Capital Fellowship, three Horton Awards, the CalArts/Herb Alpert Award in Dance, and seven consecutive NEA fellowships. He is Professor of Choreography in the UCLA Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, and for the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture he has served as Associate Dean (2014-15), Acting Dean (2015), and Interim Dean (2015-17).

The dancing in Act One was often loose limbed and in tune with Strayhorn’s music, jazzy, and the way Roussève weaves his dancers in and out of groupings was breath-taking and flawless. The work opened with dancer Kevin Le performing an introspective solo before being joined by Bernard Brown for a together but separate duet that hinted at the long-time relationship that Strayhorn had with African-American musician Aaron Bridgers. Le and Brown are both extremely talented dancers and performed Roussève’s movement with wonderful smoothness and professional ease. There was also a wonderful chemistry between the two men, connecting emotionally without doing so physically. Another dancer who demonstrated this same ease was Jasmine Jawato.

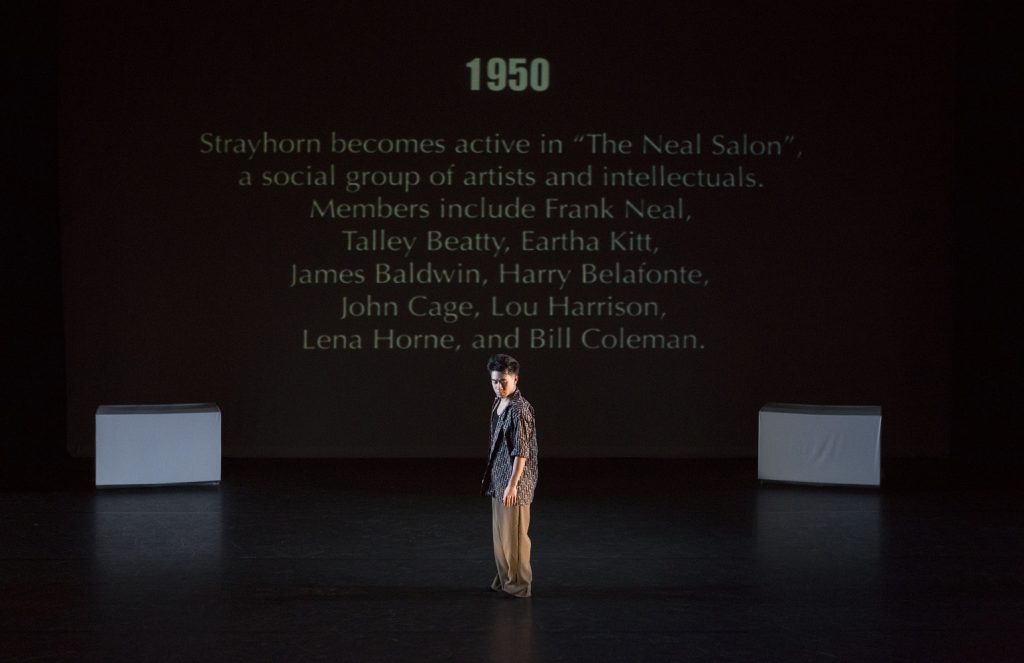

The rest of the very talented cast soon entered, everyone dressed in black to perform the first of many group sections to Strayhorn’s amazingly danceable music. Pedestrian clothing drops mysteriously from out of the sky and as we read the first of biographical information projected on the back wall, the dancers get dressed and take on a jazz nightclub atmosphere-like physicality. Stools that are lined up on either side of the stage space, act as resting places for the dancers/actors and boxes are brought in to become screens for additional projections. Strayhorn’s reasons for his activism were portrayed through videos of horrific scenes of southern black protestors being fire hosed, chased by dogs and beaten by the police during the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s.

Act One was rich with dancing built in combinations of nine dancers breaking off into different sized groupings, but it suffered with sections that bordered on becoming cute or inane. One such section was magnificently performed by Kevin Williamson playing to the audience like a vaudeville performer between acts. Other such sections seemed to belong in a different work. Maybe they were meant to relate to situations in Strayhorn’s life, but the meaning seemed lost in its abstractness.

Act Two reached deeply into the physical and emotional illness that Strayhorn struggled with. A projection of blood cells as seen through a laboratory slide was projected on the back wall as the cast stood grouped together center stage. This led to each dancer walking backwards until they exited, leaving Jawato alone for a powerful solo that showed us the pain and agony of Strayhorn’s disease. This theatrical method continued as time and movement reverse to repeat the opening duet with Brown and Le and Le’s solo that evoked Strayhorn’s final gasps of life.

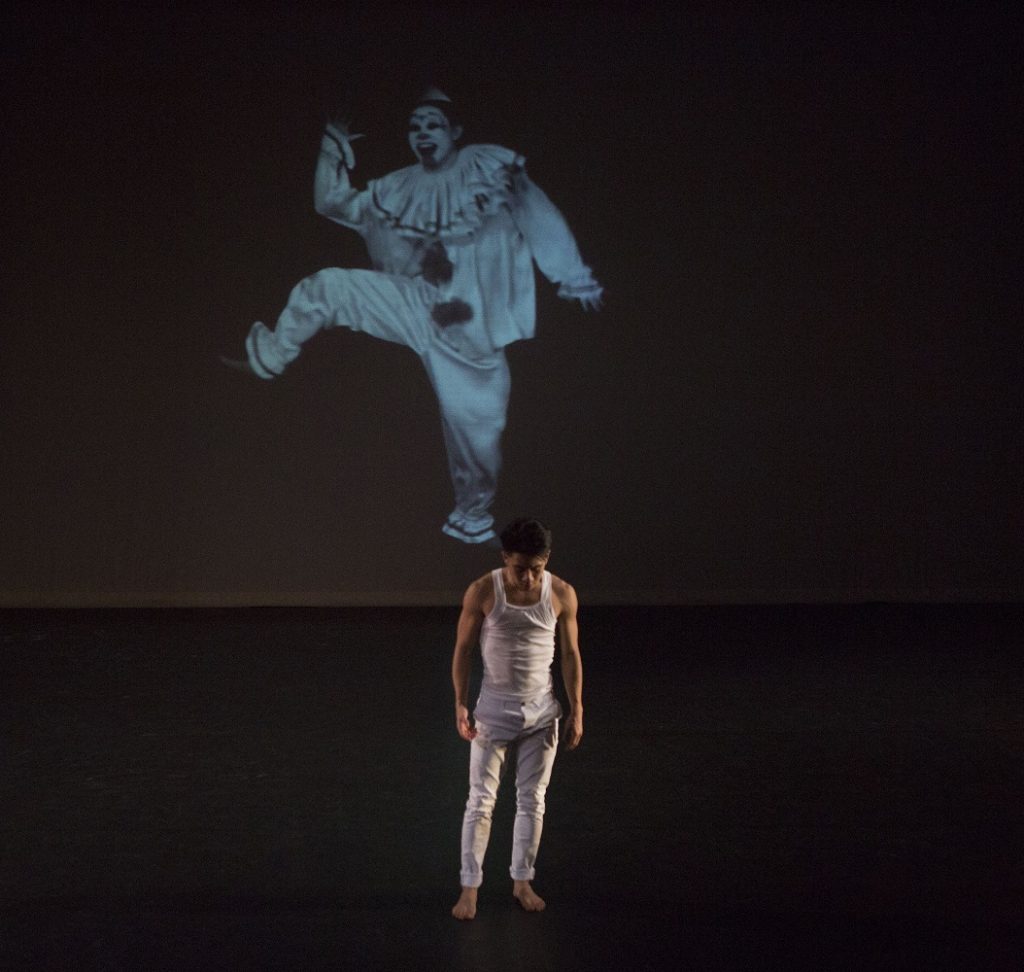

The clown, also performed by Le, was performed live and on video. I struggled with this representation of one element of Strayhorn’s persona. The devotion he showed to Ellington and the way in which he allowed himself to be overlooked, was indeed tragic, but the clown make-up felt dangerously aligned to the era’s use of black face.

Halfway To Dawn should be seen and hopefully it will mature and endure. The music of Billy Strayhorn was a joy to hear again, and it was great to learn the less-known facts about his life. The choreography was enjoyable, the costumes were appropriate but ill-fitting on some of the dancers, and the lighting was beautiful. My thoughts regarding Act One, which I first saw performed last spring at the Los Angeles Dance Platform were only re-enforced, however. As it now stands now, Act One wears progressively thin.

The beautiful and talented members of the DAVID ROUSSÉVE/REALITY performing company included Bernard Brown, Raymond Ejiofor, Dezaré Foster, Jasmine Jawato, Kevin Le, Julio Medina, Samantha Mohr, Leanne Iacovetta Poirier and Kevin Williamson.

The rest of the collaborative team artists included: Chris Kuhl (Lighting Design), Cari Ann Shim Sham* (Video Art and Screen Concept), d. Sabela Grimes (Sound Design), Leah Piehl (Costumes), Lucy Burns (Dramaturgy), and Mary Hale (Screen Design & Fabrication).

Halfway To Dawn runs through Sunday, October 7. For tickets, click here.

For information about David Roussève/Reality, click here.

Featured image: David Roussève/Reality – Halfway To Dawn – Photo: Rose Eichenbaum