In 1969, Rupert Murdoch purchased The News of the World, Nixon called on the “silent majority” to support the Vietnam War effort, and Robert R. died of HIV/Aids; the Stonewall riots sparked a movement, Richard Oakes and a group of Mohawk activists re-took Alcatraz Island, and Black Panther Party members Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were shot dead by police while presumably sleeping in their beds. Woodstock was held in upstate New York, the first Led Zepplin album was released in the U.S., and Bolshoi’s opening Convent Garden season was reviewed with a cutting critique. In the same year, Arthur Mitchell left his company in Brazil and returned to NYC to found Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Born in New York City in 1934, Mitchell began his dance training at New York City’s High School of Performing Arts where he won a full scholarship to the School of American Ballet. Joining George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet in 1955, he became the first black man to become a permanent member of a major ballet company and rose quickly to the rank of Principal Dancer during his fifteen-year career with the NYC Ballet. In light of luminous performances and clever choreography spanning 50 years, Mitchell has been the recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors, a National Medal of the Arts, a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, the New York Living Landmark Award, the Handel Medallion, the NAACP Image Award, and more than a dozen honorary degrees.

In 1968, Mitchell left his legacy dance career and returned to the U.S. to begin teaching. Citing the momentum of the Civil Rights Movement and the 1968 assassination of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as impetus, Mitchell worked with his mentor and ballet instructor the late Karel Shook to begin offering classical technique classes in a remodeled garage in Harlem. In merely a year, Dance Theatre of Harlem emerged: a touring company, training school, and arts education program which founded a changing dance form via a permanently established (and stylistically brilliant) African American company. As the New York Times explains, “With the creation of Dance Theatre of Harlem, black ballet dancers finally had a home, and a perception of what a classical ballerina could do and look like began to change.”

After a 2004 hiatus spurred by financial difficulties that lasted for nearly a decade (and which left many wondering if the company would re-emerge strong, or even at all) Dance Theatre of Harlem made its return. Led by Artistic Director and founding DTH member Virginia Johnson—the Point Magazine founder who is widely regarded as one of the greatest ballerinas of her generation (in large part due to her performances in Giselle, A Streetcar Named Desire, or Fall River Legend)—DTH’s performing arm continues to tour, presenting neoclassical and contemporary ballet that is both historically situated and remarkably fresh. This past weekend, the company performed at The Broad Stage in Santa Monica.

The evening was split into thirds—opening with a ballet and coalescing into more neoclassical works—which, though distinctly their own, were all connected by similar modes of movement and familiar stylistic decisions. Added together, the three pieces made a panoply of movement that was exciting, but not confused: a tour de force predicated not only on virtuosity but also emotional intimacy, audience engagement, and self-aware presentation.

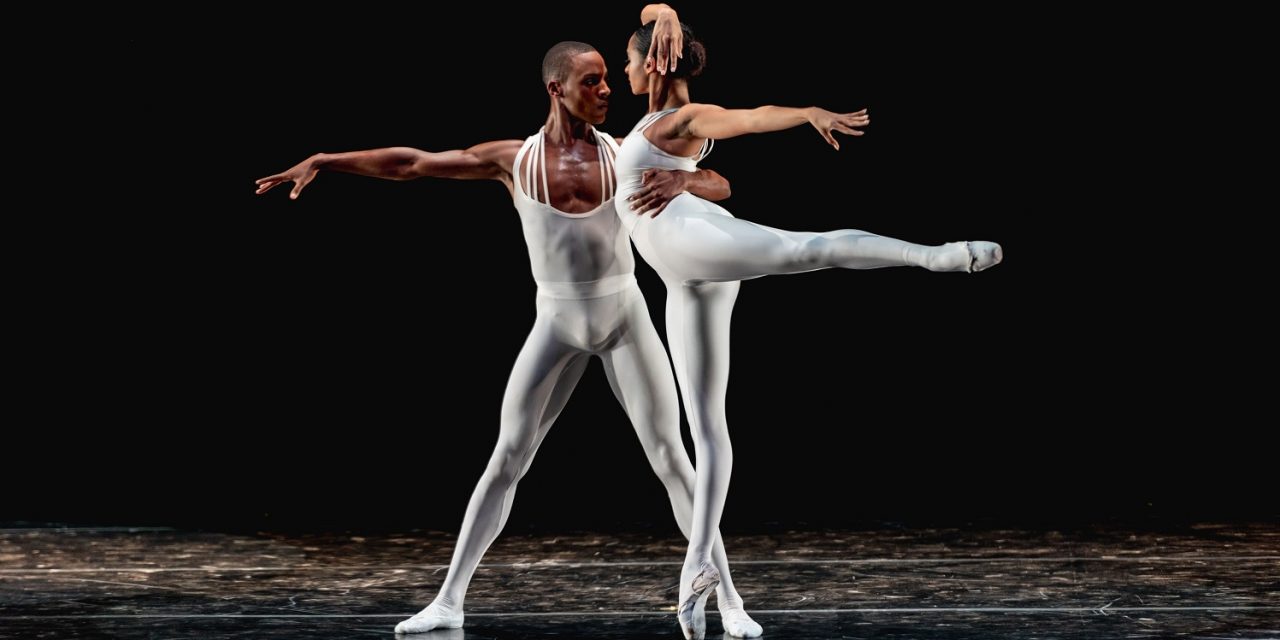

(Center) Crystal Serrano, Davon Doane – Brahms Variations – Dance Theatre of Harlem – Photo by Benn Gibbs

Brahms Variations, a ballet first premiered at the Virginia Arts Festival, was choreographed in 2016 by DTH’s resident choreographer Robert Garland. The ballet was inspired by Louis XIV, the French Patron of the Arts and Grandfather of the Western ballet canon. As explained in the company’s notes, “Arthur Mitchell was a big persona in Garland’s life, a Harlem version of the French Monarch. So, the ballet is, in part, Louis the XIV’s court meeting Harlem Swag.” Dressed in pale yellow costumes designed and executed by Pamela Allen-Cummings, the piece largely followed a series of non-narrative partnering sequences, often marked by hard blackouts in-between. Some sweet and playful, some more serious though still flirty, the patterned partnering (coupled with the classic leotards, skirts, and suit jackets) mirrored hierarchical ballet traditions, a rigidity that was softened with a score by Johannes Brahms.

Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven, a contemporary ballet piece choreographed by Ulysses Dove and set to Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, 1977, was created for the Royal Swedish Ballet in 1993 during a challenging period in Ulysses Dove’s life. Having lost 13 close friends and relatives, among them his father, Dove himself explained, “I want to tell an experience in movement, a story without words, and create a poetic monument over people I loved.” As promised by numerous re-presentations, Dove’s choreography was spare, staccato—an ample use of stillness, a change from one distinct movement to the next, a general choreographic structure which created the feeling that every moment might be the last. That is not to say the work wasn’t demanding. Each abrupt movement was technically impressive, a feat made clear by both the artistry on display and the sweat dripping down each dancer’s back.

Jorge Andres Villarini, Alicia Mae Holloway, Anthony Santos, Ingrid Silva, Dylan Santos, Lindsey Croop in Dance on the Front Porch of Heaven – Dance Theatre of Harlem – Photo by Ben Gibbs

Subtitled “Odes to Love and Loss,” Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven was as much hope-filled as it was devastating, exploring themes of individuality and mortality—and the limits of both. A deep plie sequence could have been between two friends or lovers, but the distinction seems irrelevant. Glowing white costumes designed by Jorge Gallardo and chiming church bells in Pärt’s music presented the dancers as angels or heavenly spirits, reminding viewers of Dove’s losses and calling onto the stage various streams of existentialist thought. The choreographic decision to open and close with dancers holding hands in a tight knit circle suggested themes of community and cyclicality, another take on the ouroboros; breaking the circle, and subsequently morphing into new patterns, suggested a similar cycle, a movement motif that reflected an over-arching way of using space but not an exact choreographic plan. The staging by Anne Dabrowski and the lighting design, originally done by Björn Nilsson and recreated by Peter D. Leonard, highlighted the influence of artistic direction in how viewers experience the emotions of a performance, particularly the role of lighting in shaping representations of dancers’ movements and interpersonal negotiations.

The cumulating piece Vessels, a 2014 piece choreographed by Darell Grand Moultrie and set to music by Ezio Bosso, was perhaps the masterpiece of the evening: what the company describes as drawing “on the energy and artistry of a new generation of Dance Theatre of Harlem artists.” The choreography was perfectly suited for the dancers, pushing them to their limits by giving them the parameters to shine. Grand’s knowledge of dance marked the entire performance, revealing his genius as a creative artist, while building upon the company’s legacy and new potential. Of all three pieces, it seemed the music by Ezio Bosso matched the choreography the best, pulling and pushing the dancers’ movements in a way that added texture to the entire piece. Vessels was loud and contained; aerobic and acrobatic, with jumps and partnering that could have easily fallen flat but, executed as flawlessly as they were, shone.

There were moments in the performance that could have been fleshed out—seconds in which synchronicity lacked, a few scene changes that felt too abrupt, and auditory accompaniment that pulled my focus away from the movement—but it was all in all a cohesive, outstanding performance. Characterized by striking movement motifs, the work presented by Dance Theatre of Harlem was vivid and dynamic, emblematic of what the company has built: an impeccable movement-archive showcasing exciting future artistry. Along with the choreographic richness of Garland, Dove, and Grand, Johnson’s brilliance carried through the entire performance, linking DTH’s most recent work to Mitchell’s historical vision for ballet, and promising the company will continue to shape dance as an art as well as a community-based practice.

For more information on Dance Theatre of Harlem, click here.

Feature Photo: Anthony Santos, Alicia Mae Holloway in Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven – Dance Theatre of Harlem – Photo by Ben Gibbs