According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the United States of American prison system has approximately “2.3 million people in its 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 1,852 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.” This system is often referred to as the Prison Industrial Complex and considered legalized slavery by many. On Thursday, November 29, 2019 ART + PRACTICE presented Dancing Through Prison Walls: A Conversation with Suchi Branfman and d. Sabela grimes, two very talented Los Angeles artists. The evening was eye-opening, educational, heartbreaking, infuriating, encouraging and wise. This was a clear example of how art and art activistism can bring about change to give hope to the voiceless.

Suchi Branfman is a choreographer, performer, educator and activist who in 2017 organized Inside Outside, a group of choreographers and artists who share their talents, works and inspirations with incarcerated men inside the California Rehabilitation Center, a medium-security prison in Norco, California. One of those artists is d. Sabela grimes, a “trans-media story teller, sonic ARKivist and movement composer”. It was clear from their body language that working with these men, listening to their stories and witnessing what transpired within the gymnasium where they worked, that Branfman and grimes have been forever changed. Following their presentation, so have I.

My partner and I first visited the ART + PRACTICE Exhibition Space located at 3401 W. 43rd Place in Los Angeles, to see the current exhibit titled Slavery: The Prison Industrial Complex. There were extraordinary photographs by Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormich that were beautiful to look at, but due to the subject, extremely difficult to digest. The photos were taken at the Louisiana State Penitentiary which was given the nickname “Angola” for the former slave plantation on which the prison was built. Photographs of African American men working in fields, sitting in crowded cells and being surveilled by guards with loaded guns, pierced the space from the gallery’s bare white walls. Calhoun and McCormich not only captured the inhuman situation that these men were living through, but the effects of it were painfully and hauntingly visible in their eyes.

One photo by Keith Calhoun that caught my breath showed a guard sitting on a horse overseeing male prisoners working in a crop field. The photograph’s caption read, “Who’s that man on that horse. I don’t know his name but they all call him Boss.” The photograph was dated 1980, but there were others in the exhibit that were dated as recently as 2014. This exhibit will be at the ART + PRACTICE Exhibition Space through January 5, 2019. I highly recommend that you go see and experience these photographs.

The Angola prison is one of the most notoriously brutal prisons on record. To this day, these men are treated with unnecessary brutality and cruelty. I left the gallery angry at what this system has done to our fellow humans and ashamed that the rest of us have not stepped forward to stop it.

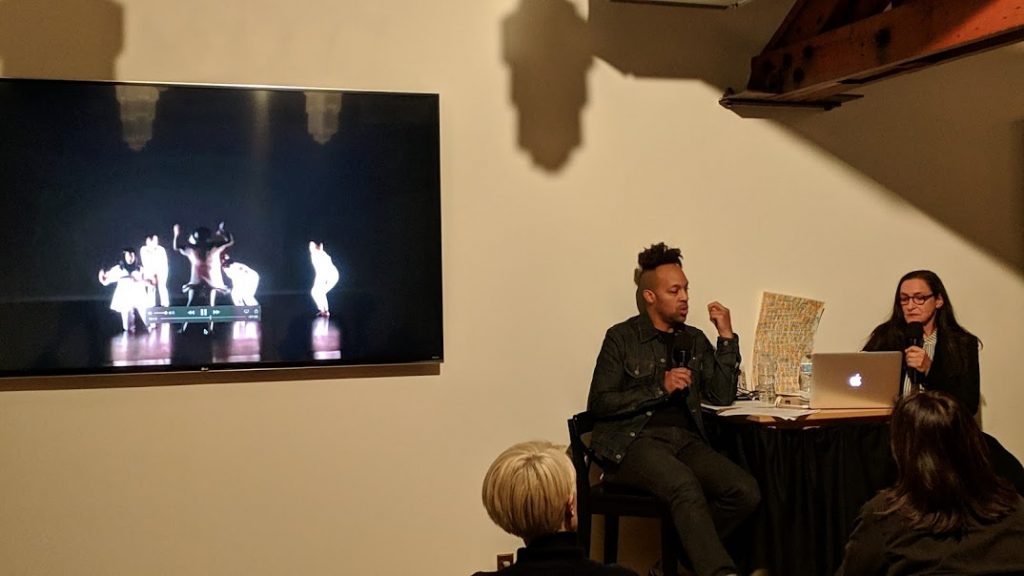

The presentation/conversation took place across the street in the elegant ART + PRACTICE Public Programs Space. Two large screen monitors hung on the wall framing grimes and Branfman who sat at a small table. We were welcomed by the ART + PRACTICE’s Deputy Director, Sophia Belsheim, who also introduced the artists and aided with the Q&A session that followed.

Branfman began by reading off a list of statistics relating to the country’s penal system, such as approximately 2.3 million people, 2.8% of our population, are incarcerated in US prisons. Following each of Branfman’s statements, grimes spoke penetrating poetry that illustrated the human side of these cold and impersonal numbers. His words gave voice to those inside those walls and to those effected on the outside; not just by the penal system, but by the social and racial injustices that have allowed the imprisonment of so many. As Branfman pointed out, this begins in high schools with students being expelled or suspended for very minor offenses.

Branfman and grimes related their experiences with the men at the Norco prison, how they were not allowed to have physical contact with these men or to get too close in proximity, and that they were always under surveillance by armed guards. They said, however, that the men they met were full of light, talented, generous and filled with hope of one day being released. The men expressed that while working with Branfman and grimes, they felt human again, momentarily released from their prison personae and thrilled to be dancing and creating movement.

One of the more poignant movement practices that Branfman described was asking the men to translate their names into movement. The other participants then learned this movement and, while standing in a circle, spoke each other’s names through dancing. Seeing this in my mind brought tears to my eyes.

Another section that stood out was grimes performing a section of his work titled BulletProof Deli that he performed for the men at Norco. It was an amazing storytelling of the black man’s experience in America and to witness grimes transform himself into these characters was truly astonishing. He said the men at Norco “Got it! They understood and recognized all the references made in the piece.”

Branfman also took other dancers into the prison to learn the movement that these men created. The prisoners were adamant that their work be learned by others to be performed on the outside. What these men wanted was to be seen and to be heard; not to be forgotten or discarded. The dance they created was given the titled SUSTAIN as the movement was inspired by what sustained them during incarceration. It was choreographed by Branfman in collaboration with the incarcerated men at the California Rehabilitation Center. The sections of SUSTAIN that we saw on video, filmed by Tom Tsai, was performed by Cynthia Irobunda, Rae Fredericks, Mailie Blume, Caroline Bourscheid, and Nia Cooper.

The discussion then turned to what was for me, the strangest event that I have heard about at any prison anywhere in this country. Taking place at the same prison in Louisiana, Angola, thousands of people flock to attend the Angola Prison Rodeo. The stadium holds up to 11 thousand people who go to watch African-American men dressed in white and black striped prison shirts perform harrowing acts with bulls and bucking horses. There is the Chariot Race with men lying on boards being pulled through the mud and animal manure by horses. The Prisoner Pinball where bulls charge at a group of men, each standing inside a medal hoop. The man who is left standing is the prize winner. Rodeo Poker consists of four men seated at a card table getting charged upon by a raging bull. The winner, if there is one, is the man who manages to remain seated.

The prizes do include money, but there are ambulances waiting outside the stadium to take the injured men to the hospital and there have been cases of fatalities. Branfman was in Louisiana doing research to go to the rodeo as part of her research for developing performative work around embodied narratives that surround the carceral world. The experience was so upsetting to Branfman that she refused to discuss or describe it at length during the evening’s discussion. She wrote the text for a poem titled Angola, reflections on a rodeo as a way of sharing the horror of what she experienced.

The rodeo also includes what resembles a flea market with tables for inmates to sell their artwork and crafts. If they have managed to sustain a good behavior status for 10 years, the men earn a table at the rodeo. They are situated behind bars, while their spouses or family members handle the sales transactions. Branfman showed us a beautiful reddish hued purse that she purchased at the rodeo that was designed and crafted by Ralph Dawson, serving life without parole at Angola Prison since 1986. She also purchased a painting Harriet Tubman…an image of her leading enslaved people out of slavery, painted by Lawrence Reed, serving life without parole at Angola.

I can certainly understand why these men take part in the rodeo. It gives them a chance to see and be seen by their wives, children and family members. It provides them an opportunity to be outside the prison walls and to feel the sun on their faces. What I find difficult to understand, aside from the family members who want to see their loved ones, are the people who pay $20 a seat to attend this brutal exhibition, this modern-day gladiator spectacle.

Do the math. With each rodeo, the prison makes approximately $220,000 and the event takes place several times a year. It is a huge source of income for the “industrial complex” owners and investors. Only a handful of the inmates make a minuscule amount of income from the experience.

During the Q&A we heard from a woman in the audience who has a family member “inside”. She spoke about and represented Families United To Stop Merged Yards, about a recent law that forces inmates to involuntarily integrate in prison yards. She expressed how these laws are making the situation within the prisons worse not better. Warring gang members are forced to mingle, bringing about more violence and causing them to receive yet longer prison time. She said that the organization is looking for lawyers, activists, volunteers, media exposure, and donations to help bring an end to this ill-fated practice. I have listed links to where one can find out more information about this group at the bottom of the article.

What Suchi Branfman and the artists that she has gathered around her are doing is nothing short of incredible. They are not merely exposing these men to art. She and her colleagues are giving a voice to these men and telling their stories. Referring to their dance SUSTAIN, one inmate said to Branfman, “Although you can’t get us out of here, you can take us out of here through your work.””

Thank you Suchi Branfman, d. Sabela grimes and all the artists involved with Inside Outside for what you are doing with these men at Norco, and for opening this writer’s eyes even further to an ugly side of America’s treatment of primarily people of color. I wish that everyone could have experienced this event so that more would get involved in bringing about change.

For more information about Suchi Branfman, click here. For d. Sabela Grimes, click here.

For more information on ART + PRACTICE, click here.

For information on photographers Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormich, click here.

To learn more about Families United To Stop Merged Yards, click here. or email them at nondpfs@gmail.com. To contact Youth Justice Coalition, email them at action@youth4justice.org.

Featured image: Inside Outside at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco, CA. – Photo by Cooper Bates

![Suchi (121 of 252)-L[1] Suchi (121 of 252)-L[1]](https://www.ladancechronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Suchi-121-of-252-L1.jpg)