In the fall of 2017, a group of choreographers and performers shared their creative process with people incarcerated inside the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC), a medium security men’s prison in Norco, CA. Curated by Suchi Branfman, the residency brought Alex Almaraz, Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, Jay Carlon, and Tom Tsai into the prison to share their work throughout the autumn months. On March 16th and 17th, they shared those pieces with people on the outside during Inside Outside: Dancing Through Prison Walls, an evening at Highways Performance Space benefiting prison abolitionist organizations Critical Resistance and the California Coalition for Women Prisoners.

Starting in the lobby, the show began with an excerpt from Tom Tsai’s Personal Persona Person, a combination of audience-participation and a lecture-demonstration which highlighted the importance of self-created choreography via an investigation of B-boy/B-girl battle culture. Tsai handed out a laminated list of terms, audience members voiced one that caught their eye, and then Tsai laid out the corresponding sequence. As he demonstrated moves such as “Dead Dog” and “T-Bone,” Tsai charismatically explained how he plays with the conventional breaking he learned off old VHS tapes.

Preserved Stories was performed by Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo and set to an audio recording of Branfman-Verissimo reading zines that CRC participants constructed when asked to think about the stories of a loved one, family member, and/or friend they thought should be preserved. Arranging chairs in a circle to signify the dancers who could not leave the prison to perform themselves, Branfman-Verissimo shifted from seat to seat as the recording repurposing the men’s zines played. Then, Branfman-Verissimo gave each audience member a special print edition with colorful text beginning “FOR EVERY LIGHT THAT SHINES SHE CONTINUES TO BE POSSITIVE…,” a material representation of the participants’ stories, histories, and memories.

Alex Swift Almaraz’s autobiographical piece Tattooed Man engaged with the life events which pushed him to work with Hip-hop. Almaraz’s choreographic choices relied a deeply emotional story; his style of movement conveyed intense vulnerability. With repetitive shaking and swaying motifs, as well as combating gestures conjuring simultaneous pride and desperation, Tattooed Man was nuanced and heart-breaking. Throughout his performance, Almaraz presented a model of art as personal language and intrapersonal communication.

There was Jay Carlon’s Sometimes I Fall, a Fluxus-inspired physical theater piece set to Apollo 11 audio. While Carlon’s work is an evening-length, site-based work co-choreographed with Lindsey Lollie and designed for a full parking lot, the piece at Highways was re-shaped to fit the space for the evening. Carlon began outside the theater and, closely followed by the audience, made his way inside by walking down an 150-foot line of masking tape, an object-oriented experiment which recalled both state-laid out realities as well as vital life-lines. Upon entering the theater, Carlon fell into a solo marked by entangled, urgent movements that probed at themes of stability, lack of privacy, mental crises, and resilience.

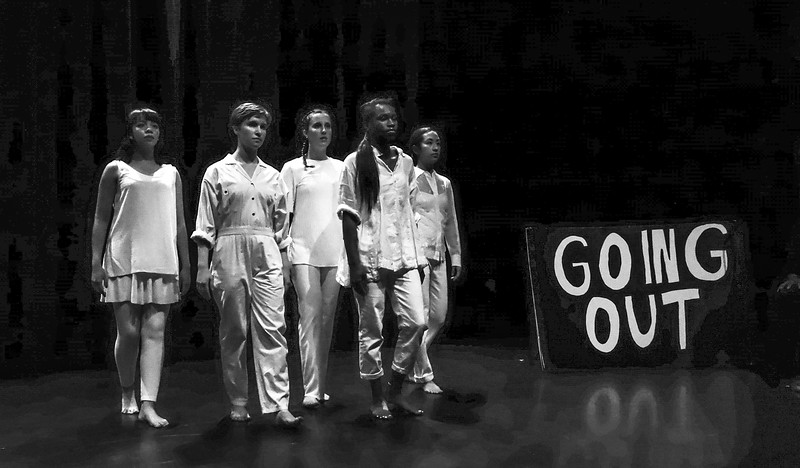

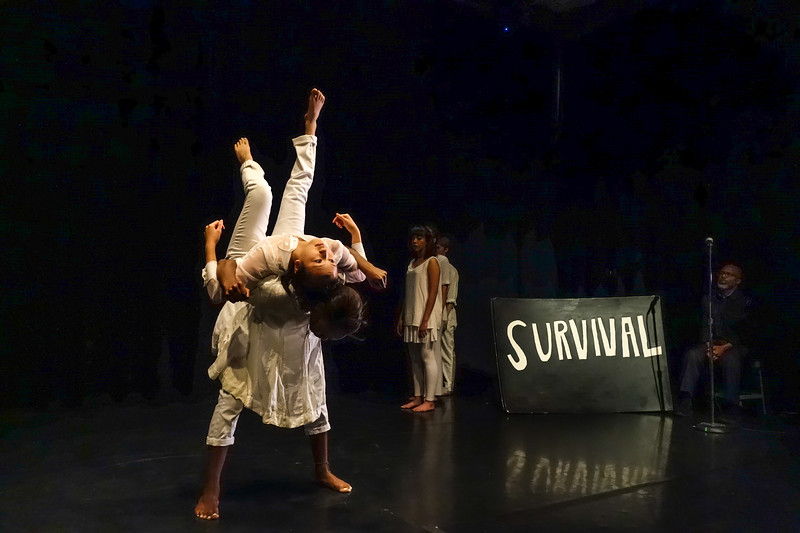

The evening concluded with Branfman’s SUSTAIN, a modern piece performed by Nia-Renee Cooper, Olivia Howie, Stephanie Lim, Amy Oden, and Anna Paz with Ernst Fenelon Jr. speaking the words of the incarcerated men who collaborated to create the work. The dance was split into sections indicated by large visuals hand-painted by Branfman-Verissimo. First, all five dancers conducted a unison walking sequence in GOING INSIDE and then a series of shaking-hands, high-fives, three second hugs, and four second kisses in CONTACT. SURVIVAL was made up of trembling solos, mirrored partnering, and tender touches; in SURVEILLANCE, the dancers watched each other and recognized that they were being seen as they repeated a movement phrase in alternating directions. Elongated limbs, swaying patterns, and free spinning imbued SUSTENANCE with hope and, mirroring the first verse, the final section GOING OUT again recalled the names and related movements of the men on the inside. SUSTAIN was charged with those who created it—Raynall, Albert, Rahman, Michael, Tieja, Mark Anthony, Aaron, Isia, Chris, William, Isaac, Cameron, Ryan, Kevin, Eden, Maile, and Rae—and the dancers in the room carried the men’s voices and movement into the space, accentuating a stark reminder that they remain unable to physically join us beyond prison walls. In Branfman’s words, it was “so strong and brave and bold…challenging and gorgeous and soft.”

Inside Outside was both performance and dialogue, an entire mode of movement that honored where the work came from by rooting itself in neoteric understandings of embodiment, physicality, and creative expression. A few days after the performance, I got the chance to talk with curator and choreographer Suchi Branfman about what art can mean for dismantling the prison industrial complex. What follows is a portion of our conversation, edited for clarity, in which we talk about the role of imagination in abolition, dancing under surveillance, and the people who remain on the inside.

TALIAH MANCINI: Where did Inside Outside originate?

SUCHI BRANFMAN: I went in to CIW (California Institute for Women) about eight years ago and spent some time with folks inside making dance and storytelling work that evolved into a piece honoring the oldest incarcerated woman in California. Then, in 2016, I went in to CRC (the men’s prison in Norco) to do a one-time…well, the prison called it a talk but I ended up dancing together with the men. It was a beautiful experience. I had performed in numerous women’s prisons throughout the country, but I had never done any work in a men’s prison. That was a Friday and the following Monday I got a call saying, “the men want you to come back and spend some time dancing inside.” That was in November of 2016 and, in January, I went back in at their request.

SUSTAIN inside CRC (men’s prison in Norco) – Suchi Branfman third from the left – Photo courtesy of the artist

What I really wanted to do was collaborate on a piece with the men on the inside. It was right after the election, and I was pondering how we would sustain ourselves. It was a concern to me as an activist, a progressive activist: how would we sustain ourselves? It was going to be a prolonged struggle, even more so than usual. It was going to be tough. “How would we sustain ourselves” was the question I was asking communities I was engaged with at the time. In November, when I first went in to CRC, that was one of the questions I asked, and it developed into, in the spring of 2017, a collaborative piece about sustenance in tough times. I crafted the piece SUSTAIN, I would say, but all the movement comes from the work we created with the folks on the inside of the CRC men’s prison. And, that was the piece that closed the concert Inside Outside.

A lot of the folks inside had never participated in any creative process like this. They really didn’t know what to call this performative dance work. “Ahhh this is Suchi stuff, and it’s cool and neat and weird and tells our stories” [laughs]. I wanted my creative collaborators to know that they are part of a community of artists that makes work that considers the world around them. We are not alone and they are now part of an international community that makes performative work that considers the world we are a part of. We all make different kinds of work, but there are lots people who all make. The main experience that most of the folks inside had was dance as a social interaction, which was so wonderful and powerful and beautiful. I don’t think that the majority of people in this country are exposed to the idea of performance and storytelling through dance. I thought, you [the men in prison] should see what’s going on and since you can’t go outside to see it, let’s see if we can’t bring it in. So, when I was asked to come back in the fall, I brought a series of guest artists for one shot deals: to share work, to have conversations about work, to do workshops, and to dance with people on the inside.

It was a lot of work. It’s always a lot of work going in to a prison, in terms of making sure everyone is cleared, that everyone is wearing the right clothing…there are a lot of rules when you go in to an institution like this. I extended an invitation to Tom, Jay, Lukaza, Alex and Sabela: “Would you be willing to go inside and share your work and then share the same work outside?” Even though we couldn’t be sitting together in the audience both inside and outside, the same work would be seen by folks on the inside and the outside. It was a poetic idea, and everyone said “yes, let’s do it.”

A space was created which could then host the other aspect of our experience. We as artists were very directly reminded of the terrifying nature of the prison industrial complex (PIC). The more dance work I’ve done inside of prisons, the more profoundly I have committed to addressing issues of mass incarceration.

MANCINI: That makes a lot of sense to me based on my take-aways from the evening: the performances worked to chip away at walls but I was also left thinking about how small that chip is and how far we have to go. The ways that you brought the people who you danced with in prison (who are still held there) into the room pushed me to think more actively about what we on the outside can be doing to continue this work.

BRANFMAN: Yes, that’s a really powerful statement. I would hope that art, in all of its variations and manifestations, would pose that question to people. What can I do to be actively engaged with this experience and in this issue? Can we imagine that we are collaborators in keeping the system going if we don’t do something to end it? I hope that folks walk away from the work with some of that sense, of being educated but also of being inspired and activated to re-imagine the world. As a group of artists, those of us in this concert talked about the fact that this experience made everyone more of an activist, if they were not already, in regards to this terrifying institution [the PIC]. So, it works both ways. The artists were engaged with an understanding that what we do can be a valuable resource in the struggle, especially working with Critical Resistance which is all about imagining a different kind of world. If you’re going to imagine abolition you really have to imagine a whole other world: a whole other way of resolving conflict, a whole other way of understanding inequality and lack of education, health care…food deserts, a whole other way of approaching every level of injustice, a way that is not based in incarceration but rather in discovering and creating solutions to social inequity.

MANCINI: Absolutely, and often when we talk about the role of imagination in abolition it gets really nebulous. We say “artists and creatives are so important to creating new worlds” but then must figure out what that actually means for various creatives or artists or writers or dancers. I found Inside Outside to be a great example of what creativity can look like and what art can do for us.

BRANFMAN: It’s imagining a way. On Saturday, we had two young, formerly incarcerated speakers who blew me away. They are activists now working with the Youth Justice Coalition and I was surprised that they sat through the whole concert and afterwards said “thank you, in the dancing I could see my life and our lives moving. I was able to see our challenges in movement and I’m so honored.” Even though no one was sharing these folks’ exact stories it was a beautiful, unpredictable result of the evening. Here were these young people starting the night saying, I came here because I was asked to be here (and of course I am happy to do that and want to do that and would love to do that), but I stayed through every second of this because it was so reflective, so inspiring, so dangerous, so caring, so brave. That was really interesting to me. If we are imagining a new world can we imagine moving the way Jay moved? Can we imagine the voices that Lukaza shared? That is the job of the artist: to invite us to access certain aspects of questions. And, I believe we can also offer concrete solutions as hopefully all of us can [laughs].

MANCINI: I think what you say about the show being “brave” and “dangerous” is interesting. Why is this type of imaginative movement, or performance, not the norm? Because this work pushes back against boundaries and structures and ideology.

BRANFMAN: Even the abolish prisons banner, I’m so happy we figured out where to hang that in the theater. It shifts the paradigm to actually be forced to see that there. Look, that’s not dangerous, that’s beautiful. A lot of people have said “what are you talking about abolish…what are you going to do with all those people who have done such awful things?” Yes, what are we going to do? When people are stealing groceries because they don’t have food, what are you going to do? When people don’t have money to pay bail, what are you going to do? There are so many questions. Can we use the model of the bravery of artists to be brave enough to come up with some other ways of framing the problems we’re faced with?

MANCINI: Earlier, you mentioned the logistic of going in to the prison. Is this another creative solution making that you engaged in? I mean, how did you navigate the surveillance of the prison system while working to create community via movement?

BRANFMAN: It is a super intense experience to be watched, constantly surveilled. It’s not even just to be watched…I draw so much inspiration from the guys who are inside. They’re the ones. Last spring, we had a whole series of experiences where they [the prison guards] felt like we were too physically close to one another. We were making duets, we were making movement, and there was no contact. I knew we couldn’t have physical contact—we could shake hands and high-five but nothing more—so the choreographic structures were very deliberate. A lot of thought went in to how we make movement together without touching each other, or without being in physical proximity. There were times when the corrections officers would tell us “step back, step away from each other” or would come up to me and say, “this is way too much, they are all too close.” I would often find myself in the terrible position of ensuring that people remembered that they couldn’t be that physical or that close together. This is a difficult position to be in, very tough to be forced to become an enforcer of the surveillance system in order to do your artistic work. It’s deeply challenging. They know me—the guards know me now. I’m not your friend.

MANCINI: Being more explicitly incorporated…

BRANFMAN: Yes, I do know people who have been doing this type of art in prisons for many years who decided they couldn’t continue to be engaged so deeply as part of the system. I can completely understand and respect that but, for me right now, it’s the guys that keep reminding me why I am doing the work and why I have decided it is worth it. I have this feeling that until there is a huge change in the carceral system I need to come to terms with my own personal contradictions. I will continue to be an activist and to bring the dance work into these circles, to make access part of our dance world.

At the beginning and end of rehearsal we always have a check-in or check-out. I have repeatedly felt the need to share that, “I feel very uncomfortable having to separate you all while you are dancing together. I apologize, I would never want to separate any of you from having a conversation or dancing with anyone here.” And, in response, the guys have said, “Stop! Don’t worry about it. This is how we live in here and we would rather be dancing than not have you do what you need to do in order for them to allow you to stay.” “You may be uncomfortable but we’re always uncomfortable. They’re continually surveilling us.” “Welcome to our world and we want you in it! So, whatever it takes, you just please do it.” I felt so bad but for them, as they said, “we’re used to it.” They’re always constrained and being trained. “We’re all always controlled, we’re always forced to be tough—but not when we’re dancing, not when we’re moving, not when there’s music playing and we’re all leaping across the gym.” [laughs] It’s too good for that to not happen. They have each said at different points, “for two hours we feel like we’re free. Like we’re out of here.”

MANCINI: That’s pretty world-shattering.

BRANFMAN: Yes. If I’m uncomfortable about some little thing I should just get over it and understand the power of moving freely while being caged, while being completely locked up. There’re so many different ways that people have talked about it, but there’s a certain softness that folks inside have pointed to. “I feel gentle, I don’t have to be the kind of me that I have to be when I walk out that gym door.” And that’s just to survive. You have to figure out a way to survive, not even with each other but within the system.

More recently, this spring we had all sorts of odd and terrible surveillance-related moments. What we end up seeing is that the men themselves find ways to be resistant, to resist in their very being. They’re told “no, you can’t stand there, you all have to be in this position. You can’t wear that, or you can’t do that” but they find a way to do that [laughs]. And they do that to survive. “We have to be ourselves. We have to find ways to hold on to who we are as people, to be whole, to have ties. We’re made to feel like animals, caged animals on a leash. And we let that happen to us.”

MANCINI: Dance at its best is freedom and happiness and no concern (or awareness) for others. If we take that definition, it’s pretty radical to put dance in a prison, a systematic space that is the exact opposite of all those things.

BRANFMAN: It’s funny you should say that because someone I was working with on the inside just said to me, “dancing in this space is a radical act. You can’t understand what this means, how defiant it is.” We are just dancing together—right? We’re doing what we as dancers do every day. And it really is the dancers that have gone in there with me who deeply understand the vast privilege that we have of being able to go into a dance studio to dance! Or hop in a car to get a quart of milk, or rest in a living room or enjoy a party or a concert…It is such a privilege and honor to be able to move freely or to move as we feel or to move even when we’re making choreography that is challenging or taking a class that is difficult. It’s the guys on the inside that remind us of this all the time; it’s through them that I’m reminded I need to keep dancing with them and also continue to be an activist for them—and for me. Those two, in my mind, go hand-in-hand. It’s deeply intertwined: the great joy and privilege and hard work of being a choreographer and dancer and mover, and the equal responsibility of making the world into the place I believe it should be.

MANCINI: There is urgency there. Maybe it’s less about will we do this work and more about how.

BRANFMAN: Yes, and understanding that there are many ways to do these things. Whether it’s in the form or the content or where you are. If it’s important to you, you will do what you do and then you’ll do it again and do it again and then you’ll keep doing it, and it’ll get nothing but better as you go. It’s a marathon not a sprint. It’s a marathon of work. Every dance doesn’t have to be your best dance it just has to be the best you can do—with clarity and commitment [laughs].